Detroit Institute of Arts

| |

| |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | 1885 |

|---|---|

| Location | 5200 Woodward Avenue Detroit, Michigan |

| Coordinates | 42°21′33.912″N 83°3′52.474″W / 42.35942000°N 83.06457611°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Collection size | 65,000 works[1] |

| Visitors | 677,500 (2015)[1] |

| Director | Salvador Salort-Pons |

| Public transit access | QLINE: Warren / Ferry DDOT, SMART |

| Website | www.dia.org |

Detroit Institute of Arts | |

| Built | 1927 |

| Architect | Paul Philippe Cret |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts, Italian Renaissance |

| Restored | 2007 |

| Restored by | Michael Graves |

| Part of | Cultural Center Historic District (Detroit) (ID83003791) |

| Designated CP | November 21, 1983 |

The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) is a museum institution located in Midtown Detroit, Michigan. It has one of the largest and most significant art collections in the United States. With over 100 galleries, it covers 658,000 square feet (61,100 m2)[2][3] with a major renovation and expansion project completed in 2007 that added 58,000 square feet (5,400 m2). The DIA collection is regarded as among the top six museums in the United States with an encyclopedic collection which spans the globe from ancient Egyptian and European works to contemporary art.[2] Its art collection is valued in billions of dollars, up to $8.1 billion USD according to a 2014 appraisal.[4][5] The DIA campus is located in Detroit's Cultural Center Historic District, about 2 miles (3.2 km) north of the downtown area, across from the Detroit Public Library near Wayne State University.

The museum building is highly regarded by architects.[6] The original building, designed by Paul Philippe Cret, is flanked by north and south wings with the white marble as the main exterior material for the entire structure. The campus is part of the city's Cultural Center Historic District listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The museum's first painting was donated in 1883 and its collection consists of over 65,000 works. With about 677,500 visitors annually for 2015, the DIA is among the most visited art museums in the world.[1][7] The Detroit Institute of Arts hosts major art exhibitions; it contains a 1,150-seat theatre designed by architect C. Howard Crane, a 380-seat hall for recitals and lectures, an art reference library, and a conservation services laboratory.[1]

In 2023, readers of USA Today voted the Detroit Institute of Arts the No. 1 art museum in the United States.[8]

Collections

[edit]

The museum contains 100 galleries of art from around the world.[9] Diego Rivera's Detroit Industry cycle of frescoes span the upper and lower levels to surround the central grand marble court of the museum. The armor collection of William Randolph Hearst lines the main hall entry way to the grand court. The collection of American art at the DIA is one of the most impressive, and officials at the DIA have ranked the American paintings collection third among museums in the United States. Works by American artists began to be collected immediately following the museum's founding in 1883. Today the collection is a strong survey of American history, with acknowledged masterpieces of painting, sculpture, furniture and decorative arts from the 18th century, 19th century, and 20th century, with contemporary American art in all media also being collected. The breadth of the collection includes American artists including John James Audubon, George Bellows, George Caleb Bingham, Alexander Calder, Mary Cassatt, Dale Chihuly, Frederic Edwin Church, Thomas Cole, John Singleton Copley, Robert Colescott, Leon Dabo, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Thomas Eakins, Childe Hassam, Robert Henri, Winslow Homer, George Inness, Martin Lewis, Georgia O'Keeffe, Charles Willson Peale, Rembrandt Peale, Tom Phardel, Duncan Phyfe, Hiram Powers, Sharon Que, Frederic Remington, Paul Revere, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, John Singer Sargent, John French Sloan, Tony Smith, Marylyn Dintenfass, Merton Simpson, Gilbert Stuart, Yves Tanguy, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Andy Warhol, William T. Williams, Anne Wilson, Andrew Wyeth, and James McNeill Whistler.

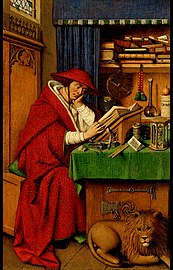

The early 20th century was a period of prolific collecting for the museum, which acquired such works as a dragon tile relief from the Ishtar Gate of Babylon, an Egyptian relief of Mourning Women and a statuette of a Seated Scribe, Pieter Bruegel the Elder's The Wedding Dance, Saint Jerome in His Study by Jan van Eyck and Giovanni Bellini's Madonna and Child. Early purchases included French paintings by Claude Monet, Odilon Redon, Eugène Boudin, and Edgar Degas, as well as Old Masters including Gerard ter Borch, Peter Paul Rubens, Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt van Rijn. The museum includes works by Vincent van Gogh including a self-portrait. The self-portrait of Vincent van Gogh and The Window by Henri Matisse were purchased in 1922 and were the first paintings by these two artists to enter an American public collection. Later important acquisitions include Hans Holbein the Younger's Portrait of a Woman, James Abbott McNeill Whistler's Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, and works by Paul Cézanne, Eugène Delacroix, Auguste Rodin, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux and François Rude. German Expressionism was embraced and collected early on by the DIA, with works by Heinrich Campendonk, Franz Marc, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Max Beckmann, Karl Hofer, Emil Nolde, Lovis Corinth, Ernst Barlach, Georg Kolbe, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paula Modersohn-Becker, and Max Pechstein in the collection. Non-German artists in the Expressionist movement include Oskar Kokoschka, Wassily Kandinsky, Chaïm Soutine, Amedeo Modigliani, Giorgio de Chirico, and Edvard Munch. The Nut Gatherers by William-Adolphe Bouguereau is, by some accounts, the most popular painting in the collection.

In addition to the American and European works listed above, the collections of the Detroit Institute of Arts are generally encyclopedic and extensive, including ancient Greek, Roman, Etruscan, Mesopotamian, and Egyptian material, as well as a wide range of Islamic, African and Asian art of all media.

In December 2010, the museum debuted a new permanent gallery with special collections of hand, shadow, and string puppets along with programmable lighting and original backgrounds. The museum plans to feature puppet related events and rotation of exhibits drawn from its puppet collections.[10]

List of exhibitions

[edit]

Artists' Take on Detroit: Projects for the Tricentennial (October 19, 2001 – December 28, 2001) This exhibit celebrates Detroit's 300th anniversary by creating 10 projects that represent the city. The installations created by 15 artists include video and still photography, text and sound, and sculptures. This exhibit includes the following: Altar Mary by Petah Coyne, Strange Früt: Rock Apocrypha by Destroy All Monsters Collective, Traces of Then and Now by Lorella Di Cintio and Jonsara Ruth, Fast Forward, Play Back by Ronit Eisenbach and Peter Sparling, Riches of Detroit: Faces of Detroit by Deborah Grotfeldt and Tricia Ward, Open House by Tyree Guyton, A Persistence of Memory by Michael Hall, Relics by Scott Hocking and Clinton Snider, Blackout by Mike Kelley, Voyageurs by Joseph Wesner.[11]

Art in Focus: Celadons (January 16 – April 14) Green-glazed ceramics, also known as celadon ware, created by Suzuki Sansei are on display in each of the Asian galleries.[12]

Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence (February 24, 2002 – May 19, 2002) The exhibit contains work of the African American artist Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) and includes never before seen pieces from the Migration and the John Brown series.[13][14]

Degas and the Dance (October 20, 2002 – January 12, 2003) This exhibit includes more than 100 pieces of work created by Edgar Degas. These pieces include model stage sets, costume designs, and photographs of the dancers from the 19th-century Parisian ballet.[15]

Magnificenza! The Medici, Michelangelo and The Art of Late Renaissance Florence (March 16, 2003 – June 8, 2003) The exhibit displays art of the cultural successes of the first four Medici grand dukes of Tuscany during 1537–1631, along with their connection with Michelangelo and his art in the Late Renaissance Florence.[16]

When Tradition Changed: Modernist Masterpieces at the DIA (June 2003 – August 2003) This exhibit only contains pieces from the DIA's collection from the late 19th-century and early 20th-century and displays the different choices artists expressed themselves after 1900.[17]

Then and Now: A selection of 19th- and 20th-Century Art by African American Artists (July 2003 – August 2003) Roughly 40 objects in this exhibit, organized by the General Motors Center for African American Art, display the artistic styles of African American artists during the past two hundred years. This exhibit includes work from Joshua Johnson, Robert Scott Duncanson, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Augusta Savage, Benny Andrews, Betye Saar, Richard Hunt, Sam Gilliam, and Lorna Simpson. Allie McGhee, Naomi Dickerson, Lester Johnson, Shirley Woodson, and Charles McGee are some of the Detroit artists that were included in the installation.[18]

Art in Focus: Buddhist Sculpture (Through July 14, 2003) This exhibit contains one Buddhist sculpture in each of the Asian galleries. These sculptures symbolize enlightenment, selflessness, wisdom and tranquility.[19]

Yoko Ono's Freight Train (September 17, 2003 – July 19, 2005) Freight Train, constructed by Yoko Ono in 1999, is a German boxcar with bullet holes and is set on a section of railroad track displayed outdoors.[20][21]

Art in Focus: Mother-of-Pearl Inlaid Lacquer (Through October 13, 2003) This exhibit contains lacquer wares made from sap of lacquer trees.[22]

Style of the Century: Selected Works from the DIA's Collection (Through October 27, 2003)[23]

Some Fluxus: From the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Foundation (Through October 28, 2008) The exhibit contains works from the Fluxus group, named by artist and provocateur George Maciunas.[24]

Dance of the Forest Spirits: A Set of Native American Masks at the DIA (Through October 6, 2003) Wooden masks made in the 1940s to represent the spirit world made by the Kwakwaka’wakw (Native Americans of the Northwest coast) are displayed in the exhibit, along with interactive videos, listening stations, and computer activities.[25]

Dawoud Bey: Detroit Portraits (April 4, 2004 – August 1, 2004) Dawoud Bey's work created during a five-week residency at Chadsey High School includes large-format, color photographic portraits along with a video of students from Chadsey High School is displayed in this exhibit. Selected artwork of students from writing and art workshops that are conducted by Bey and the art faculty at Chadsey and conduct discussion will also be displayed.[26]

Pursuits and Pleasures: Baroque Paintings from the Detroit Institute of Arts (April 10, 2004 – July 4, 2004) Pieces of work by Aelbert Cuyp, Giovanni Paolo Panini, Jacob van Ruisdael, Mathieu le Nain, Claude Lorrain, Gerard Ter Borch, Frans Snyders, and Thomas Gainsborough are displayed in this exhibit, organized by the Kresge Art Museum, the Dennos Museum Center, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, and the Muskegon Museum of Art, along with the Detroit Institute of Arts.[27]

The Etching Revival in Europe: Late Nineteenth- and Early- Twentieth Century French and British Prints (May 26, 2004 – September 19, 2004) Examples of etching work of James McNeill Whistler, Francis Seymour Haden, Charles Meryon, Édouard Manet, Jean-François Millet, and Frank Brangwyn are displayed in this exhibit.[28]

The Photography of Charles Sheeler: American Modernist (September 8, 2004 – December 5, 2004) Prints from Charles Sheeler's major series are displayed in this exhibit, including images of his house and barns in Doylestown, Pennsylvania captured in 1916 and 1917; stills from the 1920 film Manhatta; photographs of Chartres Cathedral taken in 1929; and images of American industry created in the 1930s for Fortune magazine. Also displayed are Sheeler's views from the Ford Motor Company's River Rouge complex commissioned by Edsel Ford in 1927.[29]

Murano: Glass From the Olnick Spanu Collection (December 12, 2004 – February 27, 2005) The exhibit displays about 300 Venetian blown glass pieces made in the 20th-century, organized in chronological order.[30]

Gerard ter Borch (February 27, 2005 – May 22, 2005) The exhibit contains paintings of the 17th-century Dutch life created by Gerard ter Borch.[31]

Beyond Big: Oversized Prints, Drawings and Photographs (March 16, 2005 – July 31, 2005) The exhibit displays large prints, drawings, and photographs by Abelardo Morrell, Anna Gaskell, Jenny Gage, Justin Kurland, Gregory Crewdson, Richard Diebenkorn, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenber, Judy Pfaff, Charles Burchfield, and others.[32]

Sixty-Eighth Annual Detroit Public Schools Student Exhibitions (April 9, 2005 – May 14, 2005) Kindergarten through 12th grade students will have their work displayed at the Detroit Public Library because of renovations at the DIA. This exhibit contains hundreds of ceramics, paintings, drawings, sculptures, and videos.[33]

Camille Claudel and Rodin: Fateful Encounter (October 9, 2005 – February 5, 2006) The exhibit contains work by Auguste Rodin and Camille Claude. Sixty-two sculptures by Claudel and fifty-eight by Rodin created before the two artists met along with sculptures created during the good and bad years of their relationship are displayed. Some works created by Claudel that will be displayed include Sakuntala, The Waltz, La Petite Châtelain, The Age of Maturity, The Wave, and Vertumnus and Pomona. Works of Rodin that will be displayed include Bust of Camille Claudel, Saint John the Baptist Preaching, Balzac, and The Gates of Hell.[34]

African American Art from the Walter O. Evans Collection (April 9, 2006 – July 2, 2006) Selected pieces in various media from Walter O. Evan's private collection will be displayed in the exhibit. Work by African American artists during the 19th and 20th centuries including Henry Ossawa Tanner, Edmonia Lewis, Elizabeth Catlett, Aaron Douglas, Romare Bearden, and Jacob Lawrence will be displayed as well.[35]

Sixty-Ninth Annual Detroit Public Schools Student Exhibit (April 20, 2006 – May 14, 2006) Kindergarten through 12th grade students will have their work displayed at the Detroit Public Library because of renovations at the DIA. This exhibit contains ceramics, drawings, collages, jewelry, and more.[36]

Recent Acquisitions: Prints, Drawings, and Photographs (May 17, 2006 – July 31, 2006) The exhibit contains works from the 1500s through the 2000s including prints by artists such as Giorgio Ghisi, Judy Pfaff, Terry Winters, and drawings by Adolph Menzel, and Stephen Talasnik. Work by early 20th-century photographers by Edwin Hale Lincoln, Alvin Langdon Coburn, and Tina Modotti are displayed. Work by contemporary artists Larry Fink, Candida Hofer, and Kiraki Sawi are also displayed.[37]

The Big Three in Printmaking: Dürer, Rembrandt and Picasso (September 13, 2006 – December 31, 2006) The exhibit features work of Dürer in the early 16th century, Rembrandt in the mid-17th century, and Picasso in the 20th century made of various media including wood and linoleum cuts, engraving, etching, aquatint, drypoint and lithography.[38]

Annie Leibovitz: American Music (September 24, 2006 – January 7, 2007) Annie Leibovitz's photographs of legends of roots music and younger artists influenced by them are displayed in the exhibit. Seventy portraits of hers are displayed in the exhibit, including B.B. King, Johnny Cash and June Carter, Willie Nelson, Pete Seeger, Etta James, Dolly Parton, Beck and Bruce Springsteen, Eminem, Aretha Franklin, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, and The White Stripes.[39]

Ansel Adams (March 4, 2007 – May 27, 2007) The exhibit contains over 100 black and white photographs taken by Ansel Adams ranging from the early 1900s to the 1960s. This exhibit contains photographs of landscapes, Pueblo Indians, mountain views, along with portraits of his friends Georgia O'Keeffe, John Marin, and Edward Weston.[40]

Seventieth Annual Detroit Public Schools Student Exhibition (March 31, 2007 – May 5, 2007) Kindergarten through 12th grade students will have their work displayed at the Detroit Public Library because of renovations at the DIA. This exhibit contains ceramics, drawings, collages, jewelry, and more.[41]

The Best of the Best: Prints, Drawings, and Photographs from the DIA Collection (November 23, 2007 – March 2, 2008) The DIA has chosen over 100 of the "best" prints, drawings, and photographs out of the museums 35,000 pieces of work to be displayed in the exhibit. Some pieces that will be displayed are Michelangelo's double-sided chalk and pen and ink drawing of 1508 showing decoration schemes for the Sistine Chapel ceiling; Russet Landscape by Edgar Degas from the 1890s; and Wheels by Charles Sheeler in 1939.[42]

Architecture

[edit]

Before 1920, a commission was established to choose an architect to design a new building to house the DIA's expanding collections. The commission included DIA President Ralph H. Booth, William J. Gray, architect Albert Kahn and industrialist Edsel Ford. W.R. Valentiner, the museum director, acted as art director and Clyde H. Burroughs was the secretary. The group chose Philadelphia architect Paul Philippe Cret as the lead architect and the firm of Zantzinger, Borie and Medary as associated architects, with Detroit architectural firms of Albert Kahn and C. Howard Crane contributing "advice and suggestions".[43]

The cornerstone for a new Beaux-Arts, Italian Renaissance–styled building was laid June 26, 1923, and the finished museum was dedicated October 7, 1927.[44]

In 1922, Horace Rackham donated a casting of Auguste Rodin's sculpture, The Thinker, acquired from a German collection, to the museum where it was exhibited while the new building was under construction. The work was placed in the Great Hall of the new museum building. Sometime in the subsequent years the work was moved out of the building and placed on a pedestal in front of the building, facing Woodward Avenue and the Detroit Public Library across the street which was also constructed of white marble in the Beaux-Arts, Italian Renaissance style .

The south and north wings were added in 1966 and 1971 respectively. Both were designed by Gunnar Birkerts and were originally faced in black granite to serve as a backdrop for the original white marble building. The south wing was later named in honor of museum benefactors Edsel and Eleanor Ford and the north wing for Jerome Cavanaugh who was Detroit Mayor during the expansion.[44][45]

The building also incorporates a 16th-century French Gothic chapel, donated by Ralph H. Booth.[46]

William Edward Kapp, architect for the firm of Smith, Hinchman & Grylls has been credited with interior design work on the Detroit Institute of Art.[47]

Artwork

[edit]

Edsel Ford commissioned murals by Diego Rivera for DIA in 1932.[48][49] Composed in fresco style, the five sets of massive murals are known collectively as Detroit Industry, or Man and Machine.[50] The murals were added to a large central courtyard; it was roofed over when the work was executed. The Diego Rivera murals are widely regarded as great works of art and a unique feature of the museum.[51] Architect Henry Sheply, a close friend of Cret's would write: "These [murals] are harsh in color, scale and composition. They were designed without the slightest thought given to the delicate architecture and ornament. They are quite simply a travesty in the name of art."[52] Their politically charged themes of proletariat struggle caused lasting friction between admirers and detractors.[53] During the McCarthy era, the murals survived only by means of a prominent sign which identified them as legitimate art; the sign further asserted unambiguously that the political motivations of the artist were "detestable".[49] Today the murals are celebrated as one of the DIA's finest assets, and even "one of America's most significant monuments".[54]

The building also contains intricate iron work by Samuel Yellin, tile from Pewabic Pottery, and architectural sculpture by Leon Hermant.[43]

Renovation and expansion

[edit]In November 2007, the Detroit Institute of Arts building completed a renovation and expansion at a total cost of $158 million. Architects for the renovation included the Driehaus Prize winner Michael Graves and associates along with the SmithGroup.[55] The project, labeled the Master Plan Project, included expansion and renovation of the north and south wings as well as restoration of the original Paul Cret building, and added 58,000 additional square feet, bringing the total to 658,000 square feet.[2] The renovated exterior of the north and south wings was refaced with white marble acquired from the same quarry as the marble on the main building designed by Paul Cret.[55] The major renovation of the Detroit Institute of Arts has provided a significant example of study for museum planning, function, direction, and design.[56]

History

[edit]

The Museum had its genesis in an 1881 tour of Europe made by local newspaper magnate James E. Scripps. Scripps kept a journal of his family's five-month tour of art and culture in Italy, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, portions of which were published in his newspaper The Detroit News. The series proved so popular that it was republished in book form called Five Months Abroad. The popularity inspired William H. Brearley, the manager of the newspaper's advertising department to organize an art exhibit in 1883, which was also extremely well received.

Brearly convinced many leading Detroit citizens to contribute to establish a permanent museum. It was originally named the Detroit Museum of Art. Among the donors were James E. Scripps, his brother George H. Scripps, Dexter M. Ferry, Christian H. Buhl, Gen. Russell A. Alger, Moses W. Field, James McMillan and Hugh McMillan, George H. Hammond, James F. Joy, Francis Palms, Christopher R. Mabley, Simon J. Murphy, John S. Newberry, Cyrenius A. Newcomb, Sr., Thomas W. Palmer, Philo Parsons, George B. Remick, Allan Shelden, William C. Weber, David Whitney Jr., George V. N. Lothrop, and Hiram Walker.

With much success from their first exhibit, Brearley then challenged 40 of Detroit's leading and prominent businessmen to contribute $1,000 each to help fund the building of a permanent museum. With $50,000 coming from Scripps alone, their goal was within reach. By 1888, Scripps and Brearley had incorporated Detroit Museum of Arts, filling it with over 70 pieces of artwork acquired by Scripps during his time in Europe.[57]

Lasting as a museum less than 40 years, the impact the museum had on the city of Detroit was tremendous. The Art Loan Exhibition's success in 1883 had led to the creation of a board. The purpose of the board was to raise and establish funds to build a permanent art museum in the city. Donating money to the cause were some of Detroit's biggest names, including James E. Scripps, George H. Scripps, Russell A. Alger, and Sen. Thomas Palmer. The old Detroit Museum of Art building opened in 1888 at 704 E. Jefferson Avenue (it was finally demolished in 1960). The Detroit Museum of Art board of trustees changed the name to the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1919 and a committee began raising funds to build a new location with Scripps still at the helm. The present DIA building on Woodward Avenue debuted on October 7, 1927. While not officially declared the founder of the Detroit Institute of Arts, Scripps and Brearley were indeed the founders of the DIA's predecessor, The Detroit Museum of Art. With the success of the arts, and the booming auto industry, families were flocking to the city; pushing for the need to expand the vision that Scripps had originally dreamed, a new building was raised and the DIA was born.

Another decision in 1919 that would have a lasting impact on the future of the museum was transferring ownership to the City of Detroit with the museum becoming a city department and receiving operating funds. The board of trustees became the Founder's Society a private support group that provided additional money for acquisitions and other museum needs. The museum sought the leadership of German art scholar Wilhelm Valentiner. It as under Valentiner's leadership as director that, the museum flush with money from a booming city and wealthy patrons, the size and quality of the DIA's collections grew significantly. The DIA became the first U.S. museum to acquire a van Gogh and Matisse in 1922 and Valentiner's relationship with German expressionist led to significant holdings of early Modernist art.[58]

Valentiner also reorganized how art was displayed at the museum. Breaking with the tradition of organizing artworks by their type with, for example, painting grouped together in one gallery and sculpture in another, Valentiner organized them by nation and chronology. This was recognized as being so revolutionary that the 1929 Encyclopædia Britannica used an illustration of the main floor plan of the DIA as an example of the perfect modern art museum.[58]

Support for the museum came from Detroit philanthropists such as Charles Lang Freer, and the auto barons: art and funds were donated by the Dodges, the Firestones and the Fords, especially Edsel Ford and his wife Eleanor, and subsequently their children. Robert Hudson Tannahill of the Hudson's Department Store family, was a major benefactor and supporter of the museum, donating many works during his lifetime. At his death in 1970, he bequeathed a large European art collection, which included works by Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Edgar Degas, Georges Seurat, Henri Rousseau, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brâncuși, important works of German Expressionism, a large collection of African art, and an endowment for future acquisitions for the museum. Part of the current support for the museum comes from the state government in exchange for which the museum conducts statewide programs on art appreciation and provides art conservation services to other museums in Michigan.

In 1949, the museum was among the first to return a work that had been looted by the Nazis, when it returned Claude Monet's The Seine at Asnières to its rightful owner. The art dealer from whom they had purchased it reimbursed the museum. In 2002, the museum discovered that Ludolf Backhuysen's A Man-O-War and Other Ships off the Dutch Coast, a 17th-century seascape painting under consideration for purchase by the museum, had been looted from a private European collection by the Nazis. The museum contacted the original owners, paid the rightful restitution, and the family allowed the museum to accession the painting into its collection, adding another painting to the museum's already prominent Dutch collection. In another case, Detroit Institute of Arts v. Ullin, which involved a claim concerning Vincent van Gogh's "Les Becheurs (The Diggers)" (1889), the museum successfully asserted that Michigan's three-year statute of limitations precluded the court or a jury from deciding the merits of the case.[59]

The museum was expanded with a south and north wing in 1966 and 1971, respectively, giving space for the museum to receive two big gifts in 1970, the collection of Robert Tannahill and Anna Thompson Dodge bequeathed the 18th-century French contents of the music room from her home, Rose Terrace, to the museum upon her death.[58]

As the fortunes of the city declined in the 1970s and 80s so did its ability to support the DIA. In 1975, even with reduced staff, the city was forced to close the museum for three weeks in June. The State of Michigan provided funding to reopen and over this time period the state would play an increasing role in funding the museum.[58]

A 1976 gift of $1 million from Eleanor Ford created the Department of African, Oceanic and New World Cultures.[45]

By 1990, 70 percent of the DIA's funding was coming from the State of Michigan, that year the state facing a recession and budget deficit cut funding by more than 50 percent. This resulted in the museum having to close galleries and reduce hours, a fundraising campaign led by Joseph L. Hudson was able to restore operations.[58]

In 1998, the Founder's Society signed an operating agreement with the City of Detroit that would have the Founder's Society operating as Detroit Institute of Arts, Inc take over management of the museum from the Art Department with the city retaining ownership of the DIA itself.[58]

On February 24, 2006, a 12-year-old boy stuck a piece of chewing gum on Helen Frankenthaler's 1963 abstract work The Bay, leaving a small stain. The painting was valued at $1.5 million in 2005, and is one of Frankenthaler's most important works. The museum's conservation lab successfully cleaned and restored the painting, which was returned to the gallery in late June 2006.[60]

As part of the settlement of the City of Detroit's bankruptcy, ownership of the museum was transferred to Detroit Institute of Arts, Inc., in December 2014, returning the museum to its pre-1919 status as an independent non-profit.[58]

In June 2020, Andrea Montiel de Shuman, a former DIA digital experience designer, made calls for greater racial sensitivity and honest interpretations of art suitable for young patrons came after Paul Gauguin's painting "Spirit of the Dead Watching" was included in the multi-gallery show. The painting depicted a 13-year-old Tahitian girl named Teha’amana, who Gauguin took as his wife, naked on a bed. Gauguin was 44 years old.[61] Montiel de Shuman, a Mexican woman, published an essay online announcing her resignation, citing "Spirit of the Dead Watching" as an example of the museum's sub-par engagement with nonwhite audiences.[62] Montiel de Shuman claimed the artworks' label did not address the possibility that the artist sexually abused her, gave her syphilis, and colonized her home. Montiel de Shuman, in an email to the Detroit Free Press, said "[I] asked how the DIA was preparing front-line staff to handle conversations around power dynamics, colonial abuse, and sexual assault - particularly of minors."[62] The museum did not publicly respond directly to Montiel de Shuman's resignation, but released a general statement that they "[do] not make media statements regarding individual employment matters."[62]

In 2022, in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the DIA's purchase of the first Van Gogh work to be owned by an American museum, the Self-Portrait with Straw Hat, the DIA mounted a comprehensive exhibition of his work, Van Gogh in America.[63] The exhibition received widespread press coverage, with Forbes noting that with 74 Van Gogh works, the exhibition marked the largest Van Gogh exhibition in America in a generation.[64]

Gallery

[edit]-

Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781

-

John Constable, The Glebe Farm, 1827

-

Edgar Degas, Violinist and Young Woman, 1870–1872

-

Paul Cézanne, Bathers, 1879

-

Max Pechstein, 1911, Under the Trees (Akte im Freien), oil on canvas, 73.6 x 99 cm (29 x 39 in)

-

Jan van Eyck (workshop), Saint Jerome in His Study, 1442

-

Benozzo Gozzoli, Madonna and Child, c. 1460

-

Master of the Tiburtine Sibyl, Crucifixion, 1485

-

Master of Frankfurt, The Virgin Enthroned, 15th Century

-

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Saint Christopher, 1518–20

-

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of a Nobleman, 1623

-

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Visitation, 1640

-

Corrado Giaquinto, Rest on the flight to Egypt, 1764–65

-

Paul Gauguin, Portrait of the Artist with the Idol, 1893

-

Pablo Picasso Femme assise (Melancholy Woman), 1902–03

-

Richard James Wyatt, Girl Bathing, marble, 1830–35

-

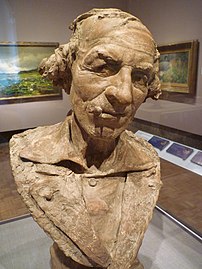

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, The Smoker, 1863

Governance

[edit]Director

[edit]The current director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, Salvador Salort-Pons a native of Madrid was previously head of the European Art Department at the DIA. Before coming to the DIA he was senior curator at the Meadows Museum at SMU and prior to that an assistant professor of art history at the Complutense University of Madrid. Salort-Pons holds a doctorate in art history from the Royal Spanish College at Italy's University of Bologna and an MBA from the Cox School of Business at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. On September 16, 2015, Salort-Pons was named as director following the retirement of Graham Beal in June.[65]

Despite the increase in yearly visitors to the DIA, some have criticized Salort-Pons in the belief that he is straying away from the "visitor-centered" philosophy pioneered by predecessor Graham Beal. Under this philosophy, the museum would make the art and interpretations of art more accessible to the general public to help them learn and connect with the pieces on display.[66] Salort-Pons' Spanish origin has made critics believe he is unable to understand and tackle the complexity of issues surrounding race, inclusivity, and representation in the United States. The New York Times reported that Salort-Pons was taking steps to improve diversity despite his limited understanding of the Black struggle in America.[67] In an interview with Artnet News, Salort-Pons said the commitment to improve diversity in the DIA included "implementing diversity and community engagement initiatives as well as hiring qualified POC candidates.[61] However, Lucy Mensah, a POC candidate hired by Salort-Pons, who served assistant curator of contemporary art in 2017, resigned due to a "toxic work environment" and believed that she and another former assistant curator were "token hires" because the DIA "premise some of their hires as a way of diversifying the voices of the institution, but at the same time they don't actually appreciate those voices."[68]

In response to criticisms of Salort-Pons in 2020, some Detroit Black community activists and members of the art community in Detroit came to his defense. The Detroit News published an article in July 2020 in which Cledie Collins Taylor, a longtime Detroit art community figure stated, regarding Salort-Pons, that "his outreach into the Black community is unprecedented." She noted further that "Having come from abroad, he was so ready to receive and know the Black community."[69]

Marketing

[edit]Besides holding major art exhibitions inside the museum's 1,150-seat theatre and annual formal entertainment fundraising galas such as Les Carnavel des ArtStars in November,[70][71] other Detroit Institute of Arts coordinated events include the annual "Fash Bash", a leading corporate sponsored fashion event, featuring celebrities and models that showcase the latest fashion trends, typically held in the Renaissance Center's Winter Garden, the Fox Theatre, or at the Detroit Institute of Arts theatre in August to celebrate Detroit Fashion Week.[72][73] A 2012 survey showed 79 percent of the institute's annual visitors lived in one of the three surrounding counties Wayne (which includes Detroit), Macomb, and Oakland.[74] The museum's annual attendance was 429,000 in 2011 and rose to 594,000 in 2013.[75] In 2014, the museum's annual attendance was about 630,000.[1]

Finance

[edit]One of the largest, most significant art museums in the United States, the Detroit Institute of Arts relies on private donations for much of its financial support. The museum has sought to increase its endowment balance to provide it financial independence. The City of Detroit owns the museum building and collection, but withdrew the city's financial support. The museum's endowment totaled $200 million in 1999 and $230 million in 2001. The museum completed a major renovation and expansion in 2007. By 2008, the museum's endowment reached $350 million; however, a recession, reduced contributions, and unforeseen costs reduced the endowment balance to critical levels.[70]

In 2012, the endowment totaled $89.3 million and provided an annual return of about $3.4 million in investment income; while admissions, the museums cafe restaurant, and merchandise and book sales from the museum's gift shop generated about $3.5 million a year, or just 15 percent of the annual budget. The museum raised $60 million from 2008 to 2012, reduced staffing, and reduced its annual operating budget from $34 million in 2008 to 25.4 million in 2012.[70][74] In 2012, voters in three of the major metropolitan counties approved a property tax levy or millage for a duration of 10 years, expected to raise $23 million per year, saving the museum from cuts. In August 2012, the museum website expressed appreciation to the voters for their support. The Museum offers Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb County residents free general admission for the 10-year duration of the millage approved in 2012.[76] In 2012, the museum established an updated fund raising goal for its endowment balance to reach $400 million by 2022 in order to be self-sustaining, while the millage is in effect.[74][77]

The DIA art collection is valued in billions of dollars, up to $8.5 billion according to a 2014 estimate.[4][5] After city's bankruptcy filing July 18, 2013, creditors targeted a part of the museum's collection that had been paid for with city funds as a potential source of revenue. Kevyn Orr, the city's state-appointed emergency manager, hired Christie's Auction House to appraise the collection. After months of determining the fair market value of the portion of the art that was purchased with city funds, Christie's released a report December 19, 2013, saying that the collection of nearly 2,800 pieces of the then city-owned artwork, was worth $454 million to $867 million, with one masterpiece by Van Gogh worth up to $150 million.[78][79] To prevent possible sale of the works, museum proponents developed what has been named the grand bargain. Under the plan, which was eventually approved, the museum would raise $100 million for its portion, nine private foundations pledged $330 million, and the state of Michigan would contribute $350 million for a total of $820 million in order to guarantee municipal workers' pensions. In return, the city of Detroit would transfer its portion of the collection and the building to the non-profit entity that already operates the museum.[80] This plan was challenged by other creditors, who claimed that it treated them unfairly and requested to conduct their own appraisal of the museum collection.[81] Some creditors came forward with offers from other parties to buy the artworks for sums higher than Christie's appraisal.[82] On May 13, 2014, Orr asked Detroit automakers to add $195 million to make the grand bargain stronger.[83] The eventual settlement did not require the DIA to sell any art.[84]

The discovery in 2014 that DIA President Graham W. J. Beal and Executive Vice President Anne Erickson received significant raises in 2014 and $50,000 bonuses in 2013 raised concerns among Wayne, Macomb and Oakland County residents.[85][86][87] The DIA board notified suburban authorities November 4, 2014, that it reimbursed the museum $90,000 for bonuses awarded to three top executives in 2013.[88]

On January 8, 2015, Beal announced he was stepping down on June 30.[89] Months later, Beal's pay continued to generate negative headlines for the DIA. Oakland County officials were at the forefront of opposition to a retroactive raise for Beal, even though the money was raised from private donations.[90][91][92] Some local lawmakers hoped to make the non-profit DIA subject to the Freedom of Information Act.[93]

Since the passing of the second millage in 2020, the DIA has been in a notably financially secure position among major American museums. In 2021, the current Director, Salort-Pons, and the chairman of the DIA Board of Directors, Eugene Gargaro, published a joint Opinion piece in Hyperallergic where they noted that the millage had created a unique funding model that allowed that museum to continue to fully employ their entire staff during the pandemic, where many other museums throughout the country were forced the lay off and furlough hundreds of employees.[94] Salort-Pons similarly noted the museum finances in a 2022 interview with the New York Times, stating that in 2022, the museum's finances have never been stronger.[95]

| Detroit Institute of Arts financials[70][74] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projections based on achieving $35 million in annual fundraising | |||||

| Category | 2013 | 2022 | 2023 | 2030 | 2038 |

| $ Fundraising Cumulative est. | 35,000,000 | 350,000,000 | 385,000,000 | 630,000,000 | 910,000,000 |

| $ Endowment Balance est. | 89,000,000 | 468,600,000 | 516,500,000 | 718,900,000 | 982,200,000 |

| $ Investment Income† | 3,400,000 | 17,800,000 | 19,600,000 | 27,300,000 | 37,300,000 |

| $ Millage | 23,000,000 | 23,000,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| $ Sales† | 2,000,000 | 2,300,000 | 3,500,000 | 4,000,000 | 4,100,000 |

| $ Operating Revenue | 28,400,000 | 43,100,000 | 23,100,000 | 31,300,000 | 41,400,000 |

| $ Annual Expenditures† | 25,400,000 | 30,200,000 | 30,800,000 | 35,400,000 | 40,900,000 |

| $ +/- | 3,000,000 | 12,900,000 | (7,700,000) | (4,100,000) | 500,000 |

| † – Annual sales estimates reflect free admission for Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb county residents for millage years. Expenditures rise about 1.9% annually for inflation. Investments yield about 3.8% annually. | |||||

Notable people

[edit]Directors

[edit]- John W. Dunsmore – First Director 1888-1891[96]

- Armand H. Griffith – Second Director 1891-1913[97]

- Clyde Huntley Burroughs – Acting, then Assistant Director 1913-1917[98]

- Charles Moore – Third Director 1914-1917[99]

- Clyde Huntley Burroughs – Fourth Director 1917-1924[100]

- Wilhelm Valentiner – Fifth Director 1924-1945[101]

- Edgar Preston Richardson – Sixth Director 1945-1962[102]

- Paul L. Grigaut – Acting director 7 months[103]

- Willis F. Woods – Seventh Director 1962-1973[104]

- Frederick J. Cummings – Eighth Director 1973-1984[105]

- Michael Kan – Acting director 14 months[106]

- Samuel Sachs, II – Ninth Director 1985-1997[107]

- Maurice Parrish – Interim Director 1997-1999[108]

- Graham W. J. Beal – Tenth Director 1999-2015[109]

- Salvador Salort-Pons - Eleventh Director 2015–Present

Curators

[edit]- Mehmet Aga-Oglu – Curator of Near Eastern Art 1929-1933[110]

- Francis Waring Robinson – Curator of European Art 1939-1947, Curator of Ancient and Medieval Art 1947-1968, Curator of Medieval Art 1968-1972[111]

- William H. Peck – Curator of Ancient Art 1968-2004[112]

- Sam Wagstaff – Curator of Contemporary Art 1968-1971[113]

Bulletin

[edit]A museum bulletin has been published under three different titles since 1904:[114]

- 1948–present: Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts

- 1919–1948: Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts of the City of Detroit

- 1904–1919: Bulletin of the Detroit Museum of Arts

See also

[edit]- Cranbrook Art Museum

- Edsel and Eleanor Ford House

- List of art museums

- List of largest art museums

- List of most visited art museums

- University of Michigan Museum of Art

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Museum Fact Sheet — The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c "About the DIA". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ "DIA's collection has national luster". The Detroit News. November 6, 2007. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Randy (July 28, 2014). "New Appraisal Sets Value of Detroit Institute Artworks at Up to $8.5 Billion". The New York Times. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ a b Gibson, Eric (July 15, 2014). "A Dose of Common Sense for Detroit". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ AIA Detroit Urban Priorities Committee (January 10, 2006). "Look Inside: Top 10 Detroit Interiors". Model D Media. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Visitor Figures 2013: Museum and exhibition attendance numbers compiled and analysed" (PDF). The Art Newspaper, International Edition. April 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Amber Gibson (February 24, 2023). "10 best art museums in the US". USA Today. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ "Art at the DIA". The Detroit Institute of Arts. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ "The Puppets Are Coming, The Puppets Are Coming! Detroit Institute of Arts to unveil new puppet gallery December". Detroit Institute of Arts (Press release). November 22, 2010. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ "Artists' Take on Detroit: Projects for the Tricentennial — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Art in Focus: Celadons — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Over The Line, The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Over the Line. The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence – Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) – Art of the day". Art-of-the-day.info. May 19, 2002. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Degas and the Dance — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Magnificenza! The Medici, Michelangelo and The Art of Late Renaissance Florence — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "When Tradition Changed: Modernist Masterpieces at the DIA — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Then and Now: A Selection of 19th- and 20th-Century Art by African American Artists — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Art in Focus: Buddhist Sculpture — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Yoko Ono's Freight Train — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Yoko Ono's Freight Train on DIA's South Lawn". Imaginepeace.com. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Art in Focus: Mother-of-Pearl Inlaid Lacquer — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Style of the Century: Selected Works from the DIA's Collection — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Some Fluxus: From the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Foundation — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Dance of the Forest Spirits: A Set of Native American Masks at the DIA — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. October 6, 2003. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Dawoud Bey: Detroit Portraits — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Pursuits and Pleasures: Baroque Paintings from the Detroit Institute of Arts — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "The Etching Revival in Europe: Late Nineteenth-and Early-Twentieth Century French and British Prints — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "The Photography of Charles Sheeler: American Modernist — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Murano: Glass From the Olnick Spanu Collection — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Gerard ter Borch: Master Works, Feb. 27 – May 22". Detroit Institute of Arts. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Beyond Big: Oversized Prints, Drawings and Photographs — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Sixty-Eighth Annual Detroit Public Schools Student Exhibitions — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Camille Claudel and Rodin: Fateful Encounter — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "African American Art from the Walter O. Evans Collection — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "69th Annual Detroit Public Schools Student Exhibition — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Recent Acquisitions: Prints, Drawings, and Photographs — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "The Big Three in Printmaking: Dürer, Rembrandt and Picasso — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Annie Leibovitz: American Music — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Ansel Adams — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "70th Annual Detroit Public Schools Student Exhibition — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "The Best of the Best: Prints, Drawings, and Photographs from the DIA Collection — Events & Exhibitions at The Detroit Institute of Arts". Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ a b The Architecture of the Detroit Institute of Arts. 1928.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ferry, W. Hawkins (October 1, 2012). The Buildings of Detroit: A History. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 220–222. ISBN 978-0-8143-1665-8.

- ^ a b "It All Began with an Art Show". The Detroit News. November 6, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ "Chapel". Detroit Institute of Arts. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Witsil, Frank (June 15, 2021). "Downton Abbey fame leads to Meadow Brook Hall architect getting credit he deserves". Detroit Free Press.

- ^ Berman, Ann E. (July 2001). "The Edsel & Eleanor Ford House". Architectural Digest. Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Schjeldahl, Peter (November 28, 2011). "The Painting on the Wall". The New Yorker. pp. 84–85. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ Stremmel, Kerstin (2004). Realism. Taschen. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-3-8228-2942-4. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ Baulch, Vivian; Patricia Zacharias (July 11, 1997). "The Rouge plant – the art of industry". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ White, Theo B. (1973). Paul Philippe Cret: Architect and Teacher. Philadelphia: The Art Alliance Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-8798-2008-4. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Gonyea, Don (April 22, 2009). "Detroit Industry: The Murals of Diego Rivera". NPR. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ Freudenheim, Tom L. (August 14, 2010). "When the Motor City Was a Symbol of Strength". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ a b Ament, Lucy (January 22, 2008). "The New DIA: The Architects". Model D Media. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ Linett, Peter (January 2009). "Focus on the Detroit Institute of Arts". Curator: The Museum Journal. 52 (1): 13–33. doi:10.1111/j.2151-6952.2009.tb00330.x.

- ^ "Detroit Museum of Art — Historic Detroit". Historicdetroit.org. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "A Brief History of the Detroit Institute of Arts" (PDF). Phillips Oppenheim. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ "Report Concerning Current Approaches of United States Museums To Holocaust Era Art Claims". June 25, 2015. World Jewish Restitution Organization.

- ^ "Masterpiece Back On View After Gum Incident". Detroit Institute of Arts (Press release). June 30, 2006. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ a b "'There's No One on Staff Who Can Lead': Former Detroit Institute of Arts Employees Accuse Its Director of Mismanagement and Ethics Violations". artnet News. July 17, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c Hooper, Ryan Patrick. "Detroit museum's director on leave amid allegations of toxic culture, racial harassment". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Treaster, Joseph (October 20, 2022). "In Detroit, a Look at America's Passion for van Gogh". New York Times. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ Scott, Chadd. "Historic Van Gogh Exhibition Opens In A Revitalized Detroit". Forbes. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ Hodges, Michael H. "Salort-Pons named DIA's new director". The Detroit News. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ Hodges, Michael H. (November 19, 2020). "In DIA Director Salort-Pons, a Disconnect between How He's Seen inside, Outside the Museum". The Detroit News.

- ^ Bowley, Grahama (November 19, 2020). "Has the Detroit Institute of Arts Lost Touch With Its Home Town?". The New York Times.

- ^ Bousquette, Isabelle. "DIA action group calls for museum director's resignation, says more demands forthcoming". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Hodges, Michael. "Black Detroit author and activist rises to defend DIA's Salvador Salort-Pons". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Dobrzynski, Judith H. (August 1, 2012). "Where There's a Mill, There's a Way". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Detroit Institute of Arts calendar of events". Detroit Institute of Arts. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Hodges, Michael H. (September 18, 2003). "Michigan History: Fox Theater's rebirth ushered in city's renewal". The Detroit News. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ "Fash Bash 2011 at the Detroit Institute of Arts". dbusiness.com. July–August 2012.

- ^ a b c d Cohen, Patricia (August 8, 2012). "Suburban Taxpayers Vote to Support Detroit Museum". The New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Pes, Javier; Sharpe, Emily (March 24, 2014). "Visitor figures 2013: Taipei takes top spot with loans from China". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on March 24, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Abdel-Razzaq, Laurén (August 8, 2012). "Detroit Institute of Arts tax easily passes in Wayne, Oakland". The Detroit News.

- ^ "With art collection saved, Detroit Institute of Arts looks to future". Detroit Free Press. November 9, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Christie's Values Detroit's Art At $454M-$867M". Bloomberg Businessweek. Associated Press. December 19, 2013. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ "La collection du Detroit Institute of Arts menace" [The collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts threatened]. La Journal des Arts (in French). December 13, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ "Detroit va céder le DIA... au DIA !" [Detroit will sell the DIA...to the DIA!]. La Journal des Arts (in French). January 31, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ Bomey, Nathan (May 13, 2004). "DIA seeks to block removal of artworks for valuation in bankruptcy fight". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ O'Donnell, Nathan (April 23, 2014). "Detroit Institute of Arts Grand Bargain Not Done Yet, Creditors Claim to Have Purchaser Willing to Pay Nearly $2 Billion for Entire Collection". Art Law Report. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ Gray, Kathleen; Bomey, Nathan; Stryker, Mark (May 13, 2014). "Orr pleads with lawmakers for Grand Bargain cash, creditors plot legal strategy". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ Bomey, Nathan; Helms, Matt; Guillen, Joe (November 7, 2014). "Judge OKs bankruptcy plan; a 'miraculous' outcome". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ^ Laitner, Bill (October 23, 2014). "DIA pay raises prompt leaders to demand changes". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ Turk, John (October 23, 2014). "DIA board chairman meets with Commission, hears communities' concerns over executives' past raises". The Oakland Press. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ Chambers, Jennifer (October 23, 2014). "Oakland Co. officials demand DIA return bonuses". The Detroit News. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ Chambers, Jennifer (November 6, 2014). "DIA board pays back $90K for execs' 2013 bonuses". The Detroit News. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ "Graham Beal's plans after DIA retirement up in air". The Detroit News. Associated Press. January 8, 2015.

- ^ Brasier, L.L.; Stryker, Mark (August 27, 2015). "Some Oakland County officials protest DIA raises". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Welch, Sheri (September 1, 2015). "Amid criticism over bonuses and pay hikes, DIA is searching for new director". Michigan Radio.

- ^ Burns, Gus (August 26, 2015). "Hefty bonuses for top Detroit Institute of Arts execs draw criticism". Mlive.

- ^ Hotts, Mitch (August 27, 2015). "Macomb, Oakland lawmakers want DIA to be subject to Open Meetings, FOI acts". The Oakland Press. Archived from the original on August 29, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Salort-Pons, Salvador; Gargaro, Eugene (May 23, 2021). "How a Property Tax Helped Transform the Detroit Institute of Arts". Hyperallergic.

- ^ Joseph, Treaster (October 20, 2022). "A Rare Gem in a City That Has Struggled". New York Times.

- ^ Levy, Florence N., ed. (1899). American Art Annual 1898. Vol. 1. New York: The Macmillan Company. p. 190. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ "The Armand H. Griffith Records" (PDF). Detroit Institute of Arts Library. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ "C.H. Burroughs, Ex-Director of Art Institute, Dies". Detroit Free Press. October 6, 1973. p. 3C. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Peck 1991, pp. 54–55.

- ^ "The Clyde H. Burroughs Records" (PDF). Detroit Institute of Arts Library. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Sorensen, Lee R. (ed.). "Dictionary of Art Historians". Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ "The Edgar P. Richardson Records" (PDF). Detroit Institute of Arts Library. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Peck 1991, pp. 123.

- ^ Chargot, Patricia (April 14, 1974). "A Walking Tour of the Art Institute Conducted, and with Explanations, by Fred Cummings". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ "Frederick Cummings, 57, Dealer, Art Historian and Museum Chief". The New York Times. November 5, 1990. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ Peck 1991, p. 164.

- ^ Peck 1991, p. 167.

- ^ Lyman, David (July 30, 1999). "DIA's choice for a director resurrected an LA museum. Can he do that here? Graham Beal says: 'Watch this space'". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ Stryker, Mark (July 24, 1997). "Committee to lead DIA director search". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ "DIA Finding Aids- Aga-Oglu finding aid" (PDF). Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ "DIA Finding Aids- Robinson finding aid" (PDF). Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ "William H. Peck Current CV". Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ "A Finding Aid to the Samuel J. Wagstaff Papers, circa 1932-1985, in the Archives of American Art". Smithsonian Institution: Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ^ "Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts". The University of Chicago Press. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Abt, Jeffrey (2001). A Museum on the Verge: A Socioeconomic History of the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1882–2000. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2841-5.

- Abt, Jeffrey (2017). Valuing Detroit's Art Museum: A History of Financial Abandonment and Rescue. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-319-45218-0.

- Beal, Graham William John; Debra N. Mancoff; Detroit Institute of Arts Staff (2007). Treasures of the DIA: Detroit Institute of Arts. Detroit Institute of Arts. ISBN 978-0-8955-8160-0.

- Hill, Eric J.; John Gallagher (2002). AIA Detroit: The American Institute of Architects Guide to Detroit Architecture. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-3120-0.

- Meyer, Katherine Mattingly; McElroy, Martin C.P. (1980). Detroit Architecture A.I.A. Guide (Revised ed.). Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1651-1.

- Peck, William H. (1991) [1978]. The Detroit Institute of Arts: A Brief History. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8955-8135-8.

- World Jewish Restitution Organization Report Concerning Current Approaches of United States Museums To Holocaust-Era Claims. WJRO. June 25, 2015.

External links

[edit]- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Art museums and galleries in Detroit

- Art museums and galleries in Michigan

- Museums in Detroit

- Midtown Detroit

- Woodward Avenue

- Museums of American art

- Asian art museums in the United States

- Museums of ancient Greece in the United States

- African art museums in the United States

- Museums of ancient Rome in the United States

- Museums of Ancient Near East in the United States

- Museums of Dacia

- Historic district contributing properties in Michigan

- National Register of Historic Places in Detroit

- Institutions accredited by the American Alliance of Museums

- Art museums and galleries established in 1883

- 1883 establishments in Michigan

- Paul Philippe Cret buildings

- Michael Graves buildings

- Beaux-Arts architecture in Michigan

- Modernist architecture in Michigan

- Neoclassical architecture in Michigan

- Renaissance Revival architecture in Michigan

- Tourist attractions in Detroit

- FRAME Museums